Press Release

A single shot to the head took the life of the young Pakistani reporter, Arooj Iqbal, in the eastern city of Lahore in November 2019. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has retraced her steps, questioning her family, her colleagues, and the police in order to shed light on a murder that has gone completely unpunished – a tragic case revealing archaic attitudes and customs.

She wanted to be the first Pakistani woman journalist to create her own newspaper. Her dream was shattered, destroyed, in the most violent way. Arooj Iqbal will go down in Pakistan’s history as the first woman journalist to be murdered because of her work.

A few hours before the publication of the first issue of Choice, the local newspaper she had just founded, this 27-year-old woman’s lifeless body was found on 25 November in a pool of blood on a street in Lahore, eastern Pakistan’s megapolis. The leading suspect was and still is her ex-husband.

“Arooj Iqbal’s murder is a challenge for all Pakistani citizens,” said RSF’s Pakistan representative Iqbal Khattak, who conducted RSF’s field investigation. “This case is causing an impact here, where it is seen as a classic example of how the poor can be denied justice in Pakistan. I regard it as a collective failure on the part of our society, which has proved unable to get justice done for her bereaved family.”

Absence of security

“Arooj Iqbal’s brutal murder speaks to the complete absence of security in the working lives of women journalists in Pakistan, to the way they must constantly endure contempt, threats, violence and dependency on male superiors,” said Daniel Bastard, the head of RSF’s Asia-Pacific desk, who coordinated the research.

“We call on Pakistan’s highest judicial authorities to address the shocking impunity that marks this case, and we condemn the archaic practices that will lead to more women journalists being murdered in Pakistan if nothing changes.”

RSF met Tahira Begum, Arooj Iqbal’s mother, in the courtyard of their small, two-room home in the labyrinth of Old Lahore. “Arooj was clearly targeted because of her journalism work,” she immediately said. “The last time we spoke, she told me she had everything ready to open her office the next day. Unfortunately, she was murdered just before she could do this.”

It was Arooj’s brother, Yasir Iqbal, who received the tragic phone call at 10:44 p.m. on 25 November announcing that she had been killed by a shot to the head. The next morning, he filed a complaint – known in Pakistan as a First Information Report (FIR) – at Qilla Gujar Singh police station.

Violence and harassment

According to Yasir, Arooj’s murderer was none other than her ex-husband, Dilawar Ali, the owner of Anti-Crime, a newspaper specializing in crime stories for which Arooj used to work. “He wanted her to drop the idea of launching her own local newspaper,” Yasir told RSF a week after the murder. His FIR quotes him as saying: “I am dead sure that Dilawar killed my sister or had her killed.”

Three days before being murdered, Arooj had herself filed a complaint at the same police station accusing Dilawar Ali of beating and mistreating her. Her FIR is a long list of acts of harassment and violence against her by Dilawar. She visited her family the next day, 23 November, and told them she was scared because Dilawar had threatened to kill her.

Arooj had worked for Anti-Crime for a year and a half before accepting the owner’s marriage proposal. According to Arooj’s mother, her ordeal began as soon as they were married, because Dilawar immediately proved to be violent and to be “a very bad husband.”

Mastermind

Despite all the evidence against him, Dilawar was never arrested or charged. He provided the police with an alibi. He said he was in the Maldives on the evening that Arooj was murdered and did not return to Pakistan until the next day, 26 November.

But the fact that Dilawar was in the Maldives does not mean he could not have arranged for her to be murdered. “This is certainly possible,” RSF was told by Muhammad Iqbal, a police investigator who was involved in the Arooj murder investigation. He said he knew of other cases in which “the accused went abroad or even got themselves arrested for a petty crime in order to strengthen their case for non-involvement.”

RSF showed a copy of Yasir’s FIR to a retired senior police crime investigator. Asking not to be identified, he said she was clearly “perceived as a threat to someone.” And he added: “She may have had some secrets and if these secrets had been made public, they could have been extremely detrimental to this person.” He also combined this hypothesis with the fact that Arooj was going to become a direct competitor of her ex-husband (and former editor) by launching her own newspaper.

Constant threats against the family

In short, a more than convincing array of suspicions left little doubt as to the motive for the murder and, therefore, to the probability that Dilawar was the mastermind. But Dilawar was clearly powerful enough to escape ordinary justice.

Yasir began being the target of threats shortly after filing his complaint accusing Dilawar. “I was constantly receiving threats from Dilawar and his associates, and my younger brother was even confronted on a road by a group of thugs who told him there would be dire consequences if I did not back off.”

The persistence of the threats ended up scaring Tahira Begum, the mother of Arooj and Yasir. The quest for justice for her daughter was turning into a nightmare. “We kept on getting new threats,” she said. “I was terrified. I did not want my family to suffer another tragedy. The period after Arooj’s murder had been very stressful for me and had given a heart condition.”

Police complicity

In Punjab, the province of which Lahore is the capital, a feudal system still regulates many aspects of social life. The political elite operates above the law with the complicity of the police, who are often accused of being corrupt.

In the complaint she filed three days before her death, Arooj accused certain police officers of “protecting Dilawar’s interests.” Those at the bottom of the social scale are often reduced to suffering the consequences of what the powerful do, as the fate suffered by the Iqbal family has shown.

To avoid any possibility of being charged in connection with Arooj’s murder, Dilawar developed a two-fold strategy, using death threats to terrorize her brothers and mother while at the same time taking advantage of his contacts within the provincial parliament. He approached a member of Punjab Legislative Assembly, Chaudhry Shabbaz, and asked him to use his influence on the family and get them to accept an out-of-court settlement.

Parallel justice

To this end, Shabbaz used the “panchayat,” a sort of local council that is supposed to settle civil disputes. It is a system that the rich and powerful often use to escape criminal justice.

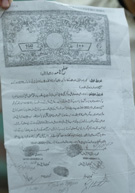

Things moved quickly. Six weeks after the murder, on 15 January 2020, an agreement was signed by Arooj’s brother Yasir, by her mother, Tahira Begum, and by the leading suspect, Dilawar Ali. RSF has a obtained a copy. At one point, it says: “I hereby swear that my family and I regard Party No. 2 [Dilawar Ali] as the culprit, that he killed my sister Arooj Iqbal or had her killed. In Panchayat, Party No.1 [Yasir] and his family decide that they all forgive Party No. 2 so that he may obtain God’s clemency. Signed: Yasir Iqbal.”

“Completely vulnerable”

Under criminal law stemming from the Islamic laws, to which the panchayats refer, conflicts are resolved by means of Qisas and Diyat. Qisas is a form of retributive justice, an “eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” Diyat consists of financial compensation, paid by the guilty person to the victim or to the victim’s family.

It was this form of agreement that Yasir Iqbal was forced to accept. The compensation for his sister’s murder was 1 million rupees, about 5,200 euros, the sum he received from Dilawar Ali. He said he signed the agreement very reluctantly. “Why did we sign?” he said. “Because Dilawar was threatening us so much, because we were completely vulnerable and because we had found the [justice] system to be completely ineffective.”

When the murder of a woman journalist is treated as an honor crime that can be settled by means of financial payment, what role is left for the legitimate authorities? To defend women who are the victims of violence in their home or at work, the Punjab provincial government created the Women’s Development Department (WDD).

Powerless authorities

“We are an observatory that monitors protection for women’s rights,” WDD deputy secretary-general Asif-ur Rehman said. When RSF asked him about the Arooj Iqbal case, he confessed that he had never heard of it.

Asked if the WDD could intervene in the case as a civil party, he said he was powerless to do this. “We have no mandate to initiate any proceedings,” he said. “If no formal complaint by the injured party or their representative is still pending, we cannot act.”

Professional isolation

Arooj’s murder elicited little or no reactions from local organizations that defend journalists. “Our family received no support from the journalistic community, none,” her mother said dejectedly.

“We did not cover Arooj’s murder as we should have done,” Punjab Union of Journalists president Qamar Bhatti conceded. He also acknowledged that the journalists’ unions and press clubs in Punjab have never taken any specific measures to protect women journalists.

It seems that Arooj Iqbal was also the victim of her relative isolation within the profession. She was probably unaware of the importance of joining a journalists’ union or press club, which is what most male journalists do in Pakistan.

Panic

Being a member of a union or press club usually means that journalists are able to mobilize their colleagues and put pressure on the authorities at the first sign of a threat. “She clearly made a strategic blunder by ignoring the union and the press club as a base of support,” said Afifa Nasar Ullah, a leading woman journalist who specializes in freelance investigative reporting.

“Also, I don’t think Arooj had undergone any safety training that could have helped her see the warning signs and improve her security. In fact, almost no women journalists who are members of unions or press clubs have received such training.” She added: “Arooj’s murder has panicked women journalists in Lahore, and has made them and the dozens of other women journalists in Punjab feel very insecure.”

Tiny minority

Women still constitute just a tiny minority of Pakistan’s journalists. According to some figures consulted by RSF, only 750 of the country’s 19,000 journalists are women – barely 4%. As a result, their specific rights as women journalists are largely ignored.

“This is unacceptable,” said Pakistani media specialist Adnan Rehmat. “Women journalists ought to receive adequate technical resources such as orientation on physical and digital security but especially training that is customized to their specific needs.”

In his view, such training should be a part of a larger strategy of solidarity and networking among women journalists. “Women journalists in several cities are already forming informal networking clusters on social media platforms such as WhatsApp to keep in touch.”

Major challenge

Rehmat added: “What needs to happen is a formal and regular engagement to bring together all women journalists in Pakistan in order to train and equip them in enacting and sustaining professional support systems including complaint mechanisms, rapid safety response, threat alerts, documentation, psychosocial counselling support and even some financial support to seek legal assistance.”

In the family home’s small courtyard, Tahira Begum talked about what drove her daughter to become a journalist. “She always liked to learn. She studied really hard while supporting herself by working and she even used to help me with the household chores. Founding her own newspaper was her dream.”

But the dream was shattered from within the journalistic community. “She had already been attacked twice in the past,” her mother added. “Once she told me she had escaped an attempt on her life. I responded by asking her to stop working as a journalist. But she said, Mom, it’s OK, nothing will happen.”

She repeated the same phrase on 23 November. Two days later, she was shot in the head.

Pakistan is ranked 145th out of 180 countries and territories in RSF’s 2020 World Press Freedom Index.

Share your comments!